Five years, and in Syria, five hundred thousands dead on, Tunisia is the only Arab Spring country where revolution didn’t get derailed. The Islamists of an-Nahda share the power with the secular party Nidaa Tounes, and despite a troublesome neighbour like Libya, despite the attempt of jihadists to undermine everything with the Bardo museum and the Sousse attacks, that swept away 85 percent of tourism, every corner here keeps intact its iconic beauty. Tunisia reminds of Europe, you are told by analysts, it is lively, free: there are cafés everywhere, you are told, their tables crowded all around the clock. And it’s true. But because they are all jobless, here. Nobody has anything to do.

Sidi Bouzid is 130 miles away from Tunis, and it is the city where it all started. The city where on December 17, 2010, street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi, 26 years old, set himself on fire following the confiscation of the fruit and vegetable cart he made a living with, fatherless, and the first of five children. He had been working since he was 10. His suicide crushed Ben Ali and shook the entire Arab world, and today the main street, here, is named after him. But that’s the only difference. Everybody, from the cafés, stares at you, surprised to see a stranger, in this stack of dust and cement and stale air in the middle of nowhere, the soil that starts to unravel into sand. The desert is a few miles away. Sidi Bouzid is one of those places where you don’t even find Chinese fakes, only second-hand stuff, at first glance you mistake the market for a dump – it’s one of those places where mothers sell on the teddy bears of their kids as soon as they grow up. Tunisia isn’t Europe here, it’s Africa. About 6,000 young men already moved to Raqqa, to the Caliphate, but not because of Islam: Tunisians join Isis to eventually get a job.

Over the last five years, the unemployement rate of Sidi Bouzid doubled from 14 to 28 percent – but the true figures, as usual, are much higher, especially because most of the times salaries are hardly enough to earn a living. The true figures are those of the twenty-somethings you see on a roof, suddenly, on a cornice, on an electricity pole: they want to commit suicide, suicide like Mohamed Bouazizi, because in the end, as they reply to those, down on the street, who try to stop them, “in the end we are already dead”. Even though, honestly, you are not impressed by poverty, here, by despair: you are rather impressed by how easily the situation could be improved. Because compared to complex countries like Lebanon, like Iraq, Yemen, Tunisia is really an exception. It hasn’t oil, which is somehow a blessing, because it means you are not a prey, like Libya, nor it has an army that like in Egypt, it’s a sort of deep state, of hidden power system that would do anything to survive. Nor it is like Syria, like Turkey: Tunisia plays a minor geopolitical role. And it has strong trade unions, that can mediate between the secular and the Islamist camp. It has an electoral law that fosters coalition governments. The new constitution was passed after a long, thought-out debate. An inclusive debate. The political difficulties of Tunisia, honestly, are nothing compared to those of fellow Arab countries.

The problem, here, is basically the economy: and it would take nothing to us, Europeans, to step in with better trade agreements, not only a Nobel prize and a pat in the back. And so? Why we just stand idly by as Tunisians kill themselves? Or run ashore dead on our islands? While we stand idly by watching the black flags increasing in number, the jihadists taking roots? Why we wait for everything to collapse?

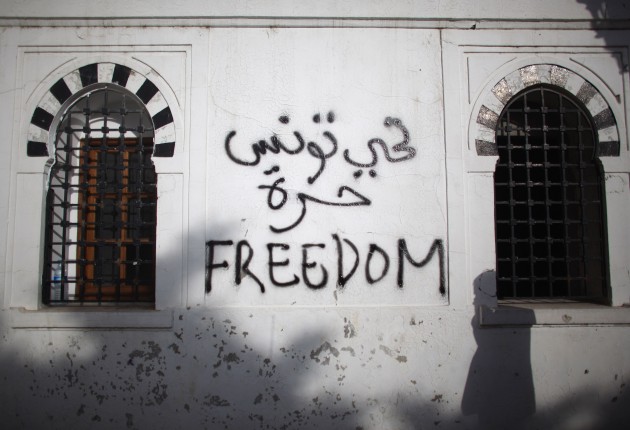

Basically, because we don’t give a shit. Democracy, freedom – the truth is that we don’t give s shit.

In these five years, our choice has been clear: to protect stability. To protect stability, at any price – even though the Middle East isn’t stable because it’s firm, but because it’s halted. Halted by force. And what we call stability, here it’s called suppression. But our only goal is to contain al-Qaeda, or whatever it evolves into over time, the Islamic State, the caliph of the day against whom everything is permitted, everything is lawful. To contain, yet, not to defeat it: because it’s actually helpful. It allows us to justify anything in an endless state of emergency, to act without the authorization of the UN, the authorization of parliaments, of wisdom, to bomb without any open discussion countries we couldn’t even locate on a map: and most of all, it allows us to keep the Arab world divided. Isis is the ideal enemy.

What we really defend, when we defend stability, is the continuity of business affairs with our local allies and partners. Italy supports al-Sisi because in Egypt it has investments worth 2,6 billion dollars, that’s all. As Cambridge doctoral student Giulio Regeni was getting tortured and murdered, and perhaps carried away in a pick up truck produced by Iveco, driven by a security agent with Fiocchi bullets in his Beretta pistol, a delegation of sixty companies was in Cairo to collect the dividends of stability. For a bunch of money, Italy is willing to be told that Giulio Regeni was a spy, that it’s been a plot of the Muslim Brotherhood, or maybe a Zionist conspiracy, a personal revenge. A car accident. Maybe he fell down the stairs. For a bunch of money, Italy sold off not only morals, but also dignity.

Every time I write about Egypt, about Syria, about Iraq, I am replied: But Arabs aren’t ready for democracy. Libya was better off under Gaddafi.

And Italy too: it was its major economic partner. And its major arms supplier. We are actually the ones who are not ready for democracy.

Articolo Precedente

In edicola sul Fatto del 25 febbraio, è nata la democrazia renziana: vincono Alfano&Verdini col 2,5%

Articolo Successivo

Zarzis – A photo